|

| RT photo |

The Crimean War of the 1850s is a murky phrase for most in the West. Something to do with

Florence Nightingale and the Charge of the Light Brigade, right? But for Russian nationalists, it is a stinging memory. As the larger geopolitical goals of the

United States and western Europe in the early 21st century seem to be focused on containing

Russia, the grievance-nursing, revanchist followers of the Russian president,

Vladimir Putin, are having flashbacks to this pivotal mid-19th-century war, when Czarist Russia, already finding the

Ottoman Empire blocking its expansion southward, also found that western European powers such as

Britain and

France were willing to block turn back its expansion toward Central Europe as well. Then, as now, attention zeroed in on

Ukraine, and in particular the Crimean Peninsula, as a place where Russia feels asked to take a stand. This time, unlike the humiliations of the Treaty of Paris, the Russian nationalists hope to win.

As we all know, Ukraine has been torn by a street-politics movement over the past several weeks. In November 2013, Ukraine’s president, Viktor Yanukovych, reneged on a promise to sign a largely symbolic “association agreement” with the European Union (E.U.). This infuriated Ukrainians who saw Yanukovych’s betrayal as a capitulation to Putin, who has long said that Ukraine is where he draws a line in the sand; he will not allow it to be swallowed up by “the West.” Already, since the implosion of the Soviet Union in 1991, the three Baltic State of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia have joined the E.U. and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Georgia and Moldova have been increasingly embraced by the United States and western Europe as allies, and even far-off Uzbekistan has hosted U.S. and NATO militaries during the Afghanistan War. Putin had been trying to woo Ukraine into eschewing E.U. aspirations in favor of a nascent customs union with Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and maybe Armenia.

|

| Yulia Tymoshenko |

Opinion on this issue tends to be split between the ethnic-Ukrainian majority and the 30% or so of the country who are culturally and linguistically Russian, especially in the east and south of the country and in and around Odessa and the capital, Kiev. It is these ethnic Russians who are the main supporters of Yanukovych, who is himself not ethnically Ukrainian but of mixed Russian, Polish, and Belarussian ancestry. Under the Party of Regions banner, Yanukovych came out ahead with a mere third or so of the national vote in the first round of the 2010 elections and in the runoff still fell short of a majority but squeaked past the pro-Western, pro-democracy opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko with a three-point margin to become president. Fearing her resurgence, Yanukovych then had Tymoshenko arrested on a variety of charges, including corruption and murder—charges which most of the international community, including the Council of Europe, regards as trumped up and politically motivated. She remains in prison and may even have been tortured.

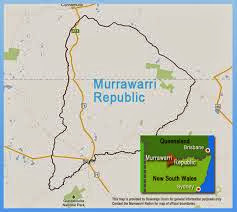

Last month, I listed Ukraine’s ethnolinguistic fault lines as one of

“Ten Separatist Movements to Watch in 2014.” Although there is nothing like a formal secession movement yet on the part of the eastern Donbas and Novorossiya (“New Russia”) regions that produced Yanukovych and most of his followers, there are other fault lines likely to emerge. Primary among these is Crimea.

In much of Ukraine, the linguistic, cultural, ethnic, and historical boundaries between Russians and Ukrainians have been blurry. Both nations claim as their patrimony the ancient monarchy of Kievan Rus’, with its capital at Kiev (Kyiv). This is why Russian nationalists regard Ukraine as part of their heartland, and this is why Ukrainians chafe at Russians who regard their nation as the mere borderlands (that is what the term Ukraine literally means) of a Russian empire. When Josef Stalin declared the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic to be nominally sovereign, it was a mere accounting trick to secure him an extra seat at the United Nations; in reality, the Ukraine was under the thumb of the party dictatorship in Moscow, like every other part of the Soviet Union. But in 1991, its status as a republic made it automatically a truly independent state. With it was Crimea, but after Stalin’s death in 1953, his successor Khrushchev transfer that territory from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (R.S.F.S.R.) to Ukraine the following year. This meant that many residents of the Crimea, who are about 58% self-identified ethnic Russians, now feel that they have landed on the wrong side of an international border when the dust settled from the end of Communism. Only about 24% of Crimean citizens are ethnically and linguistically Ukrainian.

A further 12% are Crimean Tatars, members of a Turkic-speaking, predominantly-Muslim ethnic group. (They are only tangentially related to the Tatars of Russia’s distant landlocked Republic of Tatarstan; in traditional usage, Russians called any Muslims, especially any Turkic-speaking ones, Tatars.) Crimean Tatars, who ruled the peninsula and much of today’s southern Ukraine in a medieval khanate, still dominated the peninsula demographically after absorption by the Czars, until two disasters: first, the Crimean War sent many Tatars fleeing to parts of the Ottoman Empire such as Anatolia (modern Turkey). Second, Crimea was a battleground in the Second World War, and after the war—and after the map-redrawing victors’ summit at Yalta, on the Crimean peninsula—Stalin deported thousands of Tatars to Central Asia, mostly Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, as punishment for supposed collaboration with Nazi Germany. In the 1950s, when Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, allowed many deported peoples from that era to return to their homelands, the looked-down-upon Tatars were left off the resettlement list. Their slow return to Crimea since the fall of Communism has been difficult and only partial.

|

| Modern Crimean Tatars with their flag (photo: Andriy Ignatov) |

The newly independent Ukraine in 1991 made Crimea an autonomous republic within Ukraine, the only such example. This happened only after Crimea held an unofficial referendum on independence in 1991, with 54% wanting full independence for the peninsula. Russian-speaking Crimeans assembled their own government in 1992 and agreed to “rejoin” Ukraine only with the promise of their own autonomous republic. A further agreement between Moscow and Kiev made sure that Russia’s—formerly the Soviet Union’s—Black Sea Fleet could stay in Sevastopol harbor at least into the 2040s.

|

| The Black Sea Fleet, in Crimea |

But in a sense Crimea is two autonomous republics: first, there is the

Autonomous Republic of Crimea itself, which, because it is democratic, is politically dominated by the ethnic-Russian majority. Second, there is the

Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar nation, a talking club which serves as the official voice of the Crimean Tatar people. As Maidan Square in Kiev has become the scene of larger and ever tenser demonstrations—in recent days turning lethal see photo at the top of this article)—and as Yanukovych’s pro-Russian, anti-Western police forces are using more and more violent tactics to suppress dissent, the Mejlis

has come out in favor of the pro-European demonstrators. For Russians in Crimea,

it is another story.

Very worrying has been the

confrontational language used by Russian nationalists in the autonomous republic. Crimea’s

Supreme Council, its parliament, is dominated by Yanukovych’s Party of Regions, which has 80 out of 100 seats in the body. (The second most powerful party is the

Communist Party of Ukraine, with five seats. Tymoshenko’s pro-Western, pro-democratic

Fatherland (

Batkivshchyna) party got less than 3% in the last elections in Crimea and and holds no parliamentary seats.) In a resolution adopted on January 22nd in Simferopol, the Crimean capital, the Council said that the protesters in Kiev were trying to “deprive the Autonomous Republic of Crimea of its future”—planning to strip it of its autonomy and “force Crimeans to forget the Russian language.” “We will not give Crimea to the extremists and neo-Nazis,” the statement said. Some of the strongest language came from the extremist-right-wing

Union Party (

Partia Soyuz), which warned even the blustery, pro-Yanukovych Party of the Regions against complacency and compromise, saying Crimeans (i.e. ethnic Russians in Crimea) need to be “ready for anything.”

|

| A Partia Soyuz banner |

One Soyuz deputy, Svetlana Savchenko, said, “If the national extremists [i.e., the pro-Western protest movement] seizes power, we reserve the right to decide on the determination of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. We will have nothing to do with these guys in the same country, so let them go and join Europe.” Vladimir Klychnykov, of the Party of Regions, spoke, demanding a fully federal system for Ukraine, devolving powers from Kiev to the regions. Refat Chubarov, leader of the Mejlis and one of 14 Crimean Tatar deputies in the Supreme Council, representing the tiny minority party People’s Movement of Ukraine (Narodnyi Rukh Ukrayiny), which has only five seats, accused the majority of separatism and stormed out of the chamber.

|

| Refat Chubarov, leader of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis |

In a sense, we have been here before. In 2008, nearly simultaneous with Russia’s invasion of the Republic of Georgia, meant to “liberate” the secessionist Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, there was a suspiciously groundless sudden declaration of independence by the small community of Transcarpathian Ruthenians in far-western Ukraine. At the time, Tymoshenko was prime minister and her government decried the Ruthenians’ declaration of independence a Kremlin plot—probably correctly, since it quickly evaporated. Putin’s moles were probably just testing the waters.

|

| The political divide in Ukraine in 2009. Transcarpathian Ruthenia (Zakarpattia) is shown in orange. |

But it is not merely more autonomy for itself that Crimea is worried about. It is also worried that the rest of Ukraine is

too autonomous. In a bizarre turn of events on the occasion of the 350th anniversary, on January 18th, of a territorial accord between Czarist Russia and the

Cossacks of Zaporizhia, the Crimean parliament

invoked Medieval law to claim that the independence Ukraine achieved in 1991 is somehow artificial and illegal. This agreement, the 1654 Treaty of Pereyeslav, guaranteed the territorial integrity of the

Zaporizhian Hetmanate (Host)

of Cossacks, a quasi-state loyal to

Czar Alexey I and covering roughly contemporary Ukraine—minus Crimea. The Council’s resolution proclaimed, “Reunification with Russia protected Ukraine from the national, economic, and spiritual oppression of the Catholic

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and other seekers of Ukrainian lands. That kind of ‘Europeanization’ would have meant enslavement and loss of the Orthodox faith and cultural identity to our people. Unfortunately, political gamblers who are holding forth today on the civilizational choice of Ukraine forget that such a choice has already been taken, that it was made by our ancestors many centuries ago and is based on the perennial desire of the eastern Slavonic peoples, which have the same roots, close historical ties, similar cultures and spiritual values, for unification. This choice is not revisable! We Crimeans are fully aware of the momentous significance of the Council of Pereyaslav, an event that should set an example to our contemporaries and our descendants for all time. May the day of January 18 become a symbol of peace and inseparable friendship between the brother peoples of Ukraine and Russia!”

|

| The Zaporizhian Hetmanate of Cossacks in 1654 |

Vladimir Konstantinov, speaker of the Crimean Supreme Council, added: “Attempts are being made now to make us choose our vector of integration though such a choice was taken once and for all as far back as 360 years ago at the Council of Pereyaslav. Attempts are being made today to force an artificial civilizational choice on us. Such a choice has already been taken! We are part of the Russian world. ... We—Ukraine and the Russian Federation—are parts of the same cultural and economic space. ... And no matter how hard they try to pull us apart and drag us into various ‘unions’ and ‘spaces,’ we will keep being drawn toward each other and support each other in difficult moments. If we are together we will overcome anything.”

|

| Vladimir Konstantinov, speaker of the Crimean parliament |

The long arc of history is probably in favor of those in Maidan Square demanding democracy and integration with the open societies of western Europe. But with every gain they make, the pro-Moscow jingoists in Simferopol will dig in their heels and delivery more and more fiery, Medieval-tinged demands for a restoration of the Czarist subjugation of Ukrainian people and the splitting of their peninsula from the Ukrainian republic. Eventually, it seems, something will have to give. Ukraine may yet fracture, and the battle to sort out the border between West and East may once again, 150 years later, be waged in Crimea.

[For those who are wondering, yes, this blog is tied in with a forthcoming book, a sort of encyclopedic atlas to be published by Auslander and Fox under the title Let’s Split! A Complete Guide to Separatist Movements, Independence Struggles, Breakaway Republics, Rebel Provinces, Pseudostates, Puppet States, Tribal Fiefdoms, Micronations, and Do-It-Yourself Countries, from Chiapas to Chechnya and Tibet to Texas. Look for it some time in 2014. I will be keeping readers posted of further publication news.]